Introduction

27

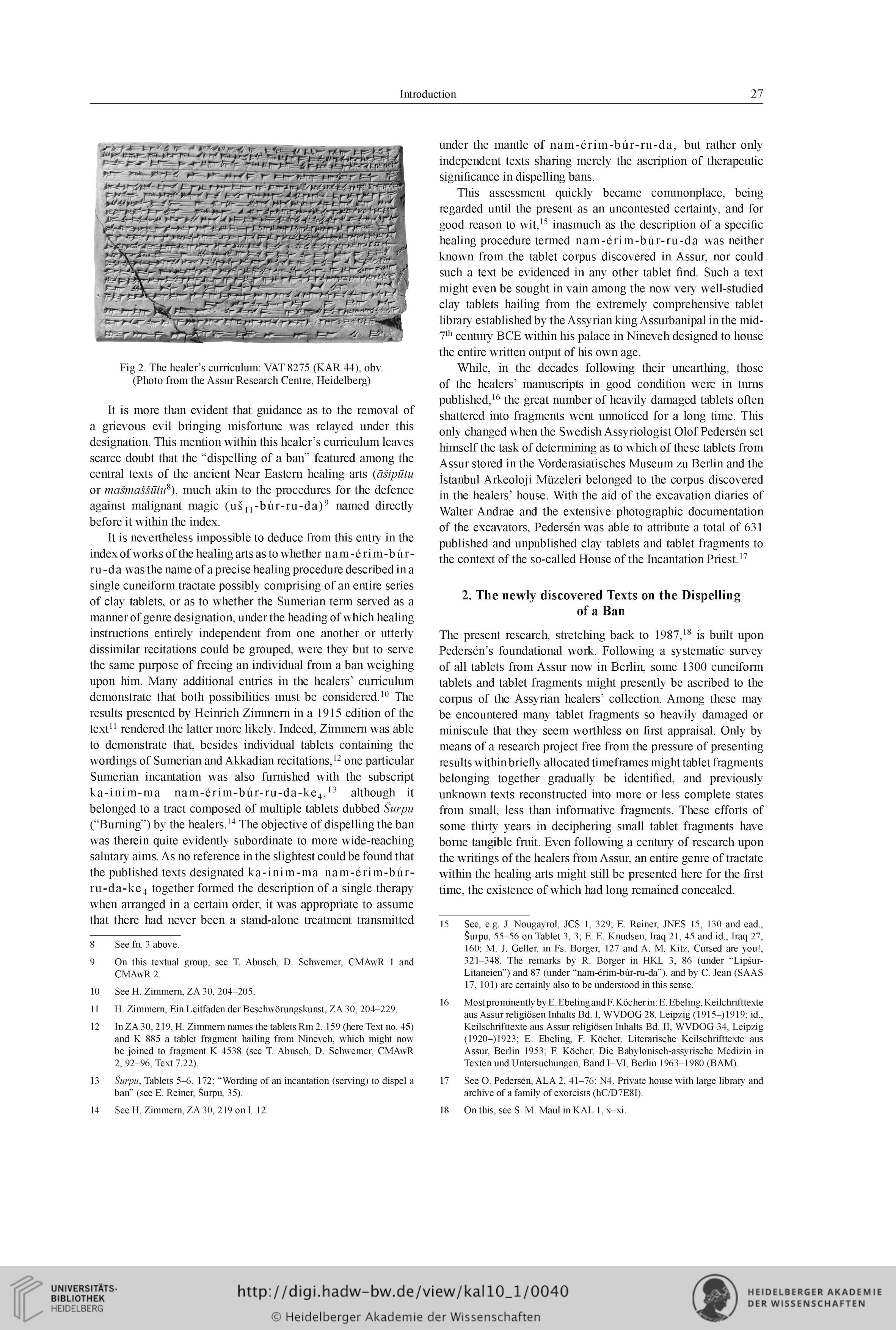

Fig 2. The healer's Curriculum: VAT 8275 (KAR 44), obv.

(Photo from the Assur Research Centre, Heidelberg)

It is more than evident that guidance as to the removal of

a grievous evil bringing misfortune was relayed under this

designation. This mention within this healer’s Curriculum leaves

scarce doubt that the ”dispelling of a ban” featured among the

central texts of the ancient Near Eastem healing arts (äsipütu

or masmassütifi). much akin to the procedures for the defence

against malignant magic (nsn-bür-ru-da)8 9 named directly

before it within the index.

It is nevertheless impossible to deduce from this entry in the

index of works of the healing arts as to whether nam-erim-bür-

ru - d a was the name of a precise healing procedure described in a

single cuneiform tractate possibly comprising of an entire series

of clay tablets, or as to whether the Sumerian term served as a

männer of gerne designation, under the heading of which healing

instructions entirely independent from one another or utterly

dissimilar recitations could be grouped, were they but to serve

the same purpose of freeing an individual from a ban weighing

upon him. Many additional entries in the healers’ Curriculum

demonstrate that both possibilities must be considered.10 The

results presented by Heinrich Zimmern in a 1915 edition of the

text11 rendered the latter more likely. Indeed, Zimmern was able

to demonstrate that, besides individual tablets containing the

wordings of Sumerian and Akkadian recitations,12 one particular

Sumerian incantation was also fumished with the subscript

ka-inim-ma nam-erim-bür-ru-da-ke4,13 although it

belonged to a tract composed of multiple tablets dubbed Surpu

("Buming”) by the healers.14 The objective of dispelling the ban

was therein quite evidently subordinate to more wide-reaching

salutary aims. As no reference in the slightest could be found that

the published texts designated ka-inim-ma nam-erim-bür-

ru-da-ke4 together formed the description of a single therapy

when arranged in a certain order, it was appropriate to assume

that there had never been a stand-alone treatment transmitted

8 See fn. 3 above.

9 On this textual group. see T. Abusch, D. Schwemer. CMAwR 1 and

CMAwR 2.

10 See H. Zimmern. ZA 30. 204-205.

11 H. Zimmern. Ein Leitfaden der Beschwönmgskunst. ZA 30. 204-229.

12 In ZA 30. 219. H. Zimmern names the tablets Rm 2. 159 (here Text no. 45)

and K 885 a tablet fragment hailing from Nineveh. which might now

be joined to fragment K 4538 (see T. Abusch. D. Schwemer. CMAwR

2. 92-96. Text 7.22).

13 Surpu, Tablets 5-6. 172: “Wording of an incantation (serving) to dispel a

bari' (see E. Reiner. Surpu. 35).

14 See H. Zimmern. ZA 30. 219 on 1. 12.

under the mantle of nam-erim-bür-ru-da. but rather only

independent texts sharing merely the ascription of therapeutic

significance in dispelling bans.

This assessment quickly became commonplace, being

regarded until the present as an uncontested certainty. and for

good reason to wit.15 inasmuch as the description of a spccific

healing procedure termed nam-erim-bür-ru-da was neither

known from the tablet corpus discovered in Assur, nor could

such a text be evidenced in any other tablet rind. Such a text

might even be sought in vain among the now very well-studied

clay tablets hailing from the extremely comprehensive tablet

library established by the Assyrian king Assurbanipal in the mid-

7th centmy BCE within his palace in Nineveh designed to house

the entire written Output of his own age.

While, in the decades following their unearthing, those

of the healers’ manuscripts in good condition were in tums

published,16 the great number of heavily damaged tablets often

shattered into fragments went unnoticed for a long time. This

only changed when the Swedish Assyriologist Olof Pedersen set

himself the task of determining as to which of diese tablets from

Assur stored in the Vorderasiatisches Museum zu Berlin and the

Istanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri belonged to the corpus discovered

in the healers’ house. With the aid of the excavation diaries of

Walter Andrae and the extensive photographic documentation

of the excavators, Pedersen was able to attribute a total of 631

published and unpublished clay tablets and tablet fragments to

the context of the so-called House of the Incantation Priest.17

2. The newly discovered Texts on the Dispelling

of a Ban

The present research. Stretching back to 1987,18 is built upon

Pedersen’s foundational work. Following a systematic survey

of all tablets from Assur now in Berlin, some 1300 cuneiform

tablets and tablet fragments might presently be ascribed to the

corpus of the Assyrian healers’ collection. Among these may

be encountered many tablet fragments so heavily damaged or

miniscule that they seem worthless on Erst appraisal. Only by

means of a research project free from the pressure of presenting

results withinbriefly allocated timeframes might tablet fragments

belonging together gradually be identiüed, and previously

unknown texts reconstructed into more or less complete States

from small, less than informative fragments. These efforts of

some thirty years in deciphering small tablet fragments have

bome tangible fruit. Even following a centmy of research upon

the writings of the healers from Assur, an entire gerne of tractate

within the healing arts might still be presented here for the Erst

time, the existence of which had long remained concealed.

15 See. e.g. J. Nougayrol. JCS 1. 329; E. Reiner. JNES 15. 130 and ead..

Surpu. 55-56 on Tablet 3. 3; E. E. Knudsen. Iraq 21. 45 and id.. Iraq 27.

160; M. J. Geller, in Fs. Borger. 127 and A. M. Kitz. Cursed are you!.

321-348. The remarks by R. Borger in HKL 3. 86 (under “Lipsur-

Litaneieri ) and 87 (under “nam-erim-bür-ru-da'), and by C. Jean (SAAS

17. 101) are certainly also to be understood in this sense.

16 Most prominently by E. Ebeling and F. Köcher in: E. Ebeling. Keilchrifttexte

aus Assur religiösen Inhalts Bd. I. WVDOG 28. Leipzig (1915—) 1919; id..

Keilschrifttexte aus Assur religiösen Inhalts Bd. II. WVDOG 34. Leipzig

(1920-)1923; E. Ebeling. F. Köcher. Literarische Keilschrifttexte aus

Assur. Berlin 1953; F. Köcher. Die Babylonisch-assyrische Medizin in

Texten und Untersuchungen. Band I-VI. Berlin 1963-1980 (BAM).

17 See O. Pedersen. ALA 2. 41-76: N4. Private house with large library and

archive of a family of exorcists (hC/D7E8I).

18 On this. see S. M. Maul in KAL 1. x-xi.

27

Fig 2. The healer's Curriculum: VAT 8275 (KAR 44), obv.

(Photo from the Assur Research Centre, Heidelberg)

It is more than evident that guidance as to the removal of

a grievous evil bringing misfortune was relayed under this

designation. This mention within this healer’s Curriculum leaves

scarce doubt that the ”dispelling of a ban” featured among the

central texts of the ancient Near Eastem healing arts (äsipütu

or masmassütifi). much akin to the procedures for the defence

against malignant magic (nsn-bür-ru-da)8 9 named directly

before it within the index.

It is nevertheless impossible to deduce from this entry in the

index of works of the healing arts as to whether nam-erim-bür-

ru - d a was the name of a precise healing procedure described in a

single cuneiform tractate possibly comprising of an entire series

of clay tablets, or as to whether the Sumerian term served as a

männer of gerne designation, under the heading of which healing

instructions entirely independent from one another or utterly

dissimilar recitations could be grouped, were they but to serve

the same purpose of freeing an individual from a ban weighing

upon him. Many additional entries in the healers’ Curriculum

demonstrate that both possibilities must be considered.10 The

results presented by Heinrich Zimmern in a 1915 edition of the

text11 rendered the latter more likely. Indeed, Zimmern was able

to demonstrate that, besides individual tablets containing the

wordings of Sumerian and Akkadian recitations,12 one particular

Sumerian incantation was also fumished with the subscript

ka-inim-ma nam-erim-bür-ru-da-ke4,13 although it

belonged to a tract composed of multiple tablets dubbed Surpu

("Buming”) by the healers.14 The objective of dispelling the ban

was therein quite evidently subordinate to more wide-reaching

salutary aims. As no reference in the slightest could be found that

the published texts designated ka-inim-ma nam-erim-bür-

ru-da-ke4 together formed the description of a single therapy

when arranged in a certain order, it was appropriate to assume

that there had never been a stand-alone treatment transmitted

8 See fn. 3 above.

9 On this textual group. see T. Abusch, D. Schwemer. CMAwR 1 and

CMAwR 2.

10 See H. Zimmern. ZA 30. 204-205.

11 H. Zimmern. Ein Leitfaden der Beschwönmgskunst. ZA 30. 204-229.

12 In ZA 30. 219. H. Zimmern names the tablets Rm 2. 159 (here Text no. 45)

and K 885 a tablet fragment hailing from Nineveh. which might now

be joined to fragment K 4538 (see T. Abusch. D. Schwemer. CMAwR

2. 92-96. Text 7.22).

13 Surpu, Tablets 5-6. 172: “Wording of an incantation (serving) to dispel a

bari' (see E. Reiner. Surpu. 35).

14 See H. Zimmern. ZA 30. 219 on 1. 12.

under the mantle of nam-erim-bür-ru-da. but rather only

independent texts sharing merely the ascription of therapeutic

significance in dispelling bans.

This assessment quickly became commonplace, being

regarded until the present as an uncontested certainty. and for

good reason to wit.15 inasmuch as the description of a spccific

healing procedure termed nam-erim-bür-ru-da was neither

known from the tablet corpus discovered in Assur, nor could

such a text be evidenced in any other tablet rind. Such a text

might even be sought in vain among the now very well-studied

clay tablets hailing from the extremely comprehensive tablet

library established by the Assyrian king Assurbanipal in the mid-

7th centmy BCE within his palace in Nineveh designed to house

the entire written Output of his own age.

While, in the decades following their unearthing, those

of the healers’ manuscripts in good condition were in tums

published,16 the great number of heavily damaged tablets often

shattered into fragments went unnoticed for a long time. This

only changed when the Swedish Assyriologist Olof Pedersen set

himself the task of determining as to which of diese tablets from

Assur stored in the Vorderasiatisches Museum zu Berlin and the

Istanbul Arkeoloji Müzeleri belonged to the corpus discovered

in the healers’ house. With the aid of the excavation diaries of

Walter Andrae and the extensive photographic documentation

of the excavators, Pedersen was able to attribute a total of 631

published and unpublished clay tablets and tablet fragments to

the context of the so-called House of the Incantation Priest.17

2. The newly discovered Texts on the Dispelling

of a Ban

The present research. Stretching back to 1987,18 is built upon

Pedersen’s foundational work. Following a systematic survey

of all tablets from Assur now in Berlin, some 1300 cuneiform

tablets and tablet fragments might presently be ascribed to the

corpus of the Assyrian healers’ collection. Among these may

be encountered many tablet fragments so heavily damaged or

miniscule that they seem worthless on Erst appraisal. Only by

means of a research project free from the pressure of presenting

results withinbriefly allocated timeframes might tablet fragments

belonging together gradually be identiüed, and previously

unknown texts reconstructed into more or less complete States

from small, less than informative fragments. These efforts of

some thirty years in deciphering small tablet fragments have

bome tangible fruit. Even following a centmy of research upon

the writings of the healers from Assur, an entire gerne of tractate

within the healing arts might still be presented here for the Erst

time, the existence of which had long remained concealed.

15 See. e.g. J. Nougayrol. JCS 1. 329; E. Reiner. JNES 15. 130 and ead..

Surpu. 55-56 on Tablet 3. 3; E. E. Knudsen. Iraq 21. 45 and id.. Iraq 27.

160; M. J. Geller, in Fs. Borger. 127 and A. M. Kitz. Cursed are you!.

321-348. The remarks by R. Borger in HKL 3. 86 (under “Lipsur-

Litaneieri ) and 87 (under “nam-erim-bür-ru-da'), and by C. Jean (SAAS

17. 101) are certainly also to be understood in this sense.

16 Most prominently by E. Ebeling and F. Köcher in: E. Ebeling. Keilchrifttexte

aus Assur religiösen Inhalts Bd. I. WVDOG 28. Leipzig (1915—) 1919; id..

Keilschrifttexte aus Assur religiösen Inhalts Bd. II. WVDOG 34. Leipzig

(1920-)1923; E. Ebeling. F. Köcher. Literarische Keilschrifttexte aus

Assur. Berlin 1953; F. Köcher. Die Babylonisch-assyrische Medizin in

Texten und Untersuchungen. Band I-VI. Berlin 1963-1980 (BAM).

17 See O. Pedersen. ALA 2. 41-76: N4. Private house with large library and

archive of a family of exorcists (hC/D7E8I).

18 On this. see S. M. Maul in KAL 1. x-xi.