Προσπάλτιοι (fr. 259)

319

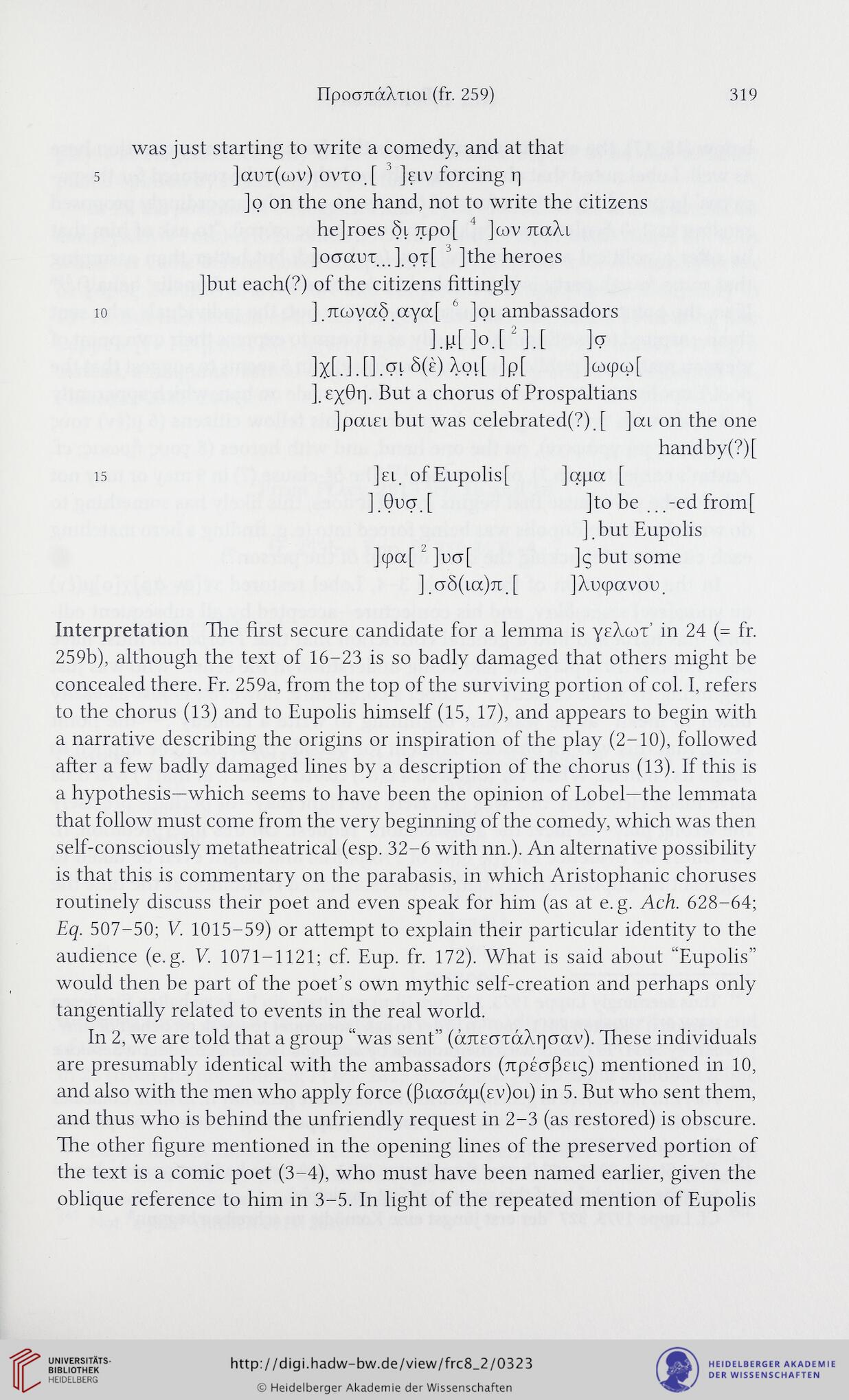

was just starting to write a comedy, and at that

5 ]αυτ(ων) ovro.f 3 ]ειν forcing η

]o on the one hand, not to write the citizens

he]roes δι προ[ 4 ]ων πάλι

]οσαυτ ,.].οτ[ 3 ]the heroes

]but each(?) of the citizens fittingly

io ] πωναδ αγα[ 6 ]oi ambassadors

].μ[]ο.[2].[ h

]χ[.].[].σιδ(έ)λοι[ ]p[ ]ωφω[

].εχθη. But a chorus of Prospaltians

]ραιει but was celebrated(?)_ [ ]αι on the one

handby(?)[

is ]ει. of Eupolis [ ]αμα [

].θυσ.[ ]to be -ed fromf

].but Eupolis

]φα[ 2 ]υσ[ ]ς but some

].σδ(ια)π.[ ]λυφανου.

Interpretation The first secure candidate for a lemma is γελωτ’ in 24 (= fr.

259b), although the text of 16-23 is so badly damaged that others might be

concealed there. Fr. 259a, from the top of the surviving portion of col. I, refers

to the chorus (13) and to Eupolis himself (15, 17), and appears to begin with

a narrative describing the origins or inspiration of the play (2-10), followed

after a few badly damaged lines by a description of the chorus (13). If this is

a hypothesis—which seems to have been the opinion of Lobel—the lemmata

that follow must come from the very beginning of the comedy, which was then

self-consciously metatheatrical (esp. 32-6 with nn.). An alternative possibility

is that this is commentary on the parabasis, in which Aristophanic choruses

routinely discuss their poet and even speak for him (as at e. g. Ach. 628-64;

Eq. 507-50; V. 1015-59) or attempt to explain their particular identity to the

audience (e. g. V. 1071-1121; cf. Eup. fr. 172). What is said about “Eupolis”

would then be part of the poet’s own mythic self-creation and perhaps only

tangentially related to events in the real world.

In 2, we are told that a group “was sent” (άπεστάλησαν). These individuals

are presumably identical with the ambassadors (πρέσβεις) mentioned in 10,

and also with the men who apply force (βιοισάμ(εν)οι) in 5. But who sent them,

and thus who is behind the unfriendly request in 2-3 (as restored) is obscure.

The other figure mentioned in the opening lines of the preserved portion of

the text is a comic poet (3-4), who must have been named earlier, given the

oblique reference to him in 3-5. In light of the repeated mention of Eupolis

319

was just starting to write a comedy, and at that

5 ]αυτ(ων) ovro.f 3 ]ειν forcing η

]o on the one hand, not to write the citizens

he]roes δι προ[ 4 ]ων πάλι

]οσαυτ ,.].οτ[ 3 ]the heroes

]but each(?) of the citizens fittingly

io ] πωναδ αγα[ 6 ]oi ambassadors

].μ[]ο.[2].[ h

]χ[.].[].σιδ(έ)λοι[ ]p[ ]ωφω[

].εχθη. But a chorus of Prospaltians

]ραιει but was celebrated(?)_ [ ]αι on the one

handby(?)[

is ]ει. of Eupolis [ ]αμα [

].θυσ.[ ]to be -ed fromf

].but Eupolis

]φα[ 2 ]υσ[ ]ς but some

].σδ(ια)π.[ ]λυφανου.

Interpretation The first secure candidate for a lemma is γελωτ’ in 24 (= fr.

259b), although the text of 16-23 is so badly damaged that others might be

concealed there. Fr. 259a, from the top of the surviving portion of col. I, refers

to the chorus (13) and to Eupolis himself (15, 17), and appears to begin with

a narrative describing the origins or inspiration of the play (2-10), followed

after a few badly damaged lines by a description of the chorus (13). If this is

a hypothesis—which seems to have been the opinion of Lobel—the lemmata

that follow must come from the very beginning of the comedy, which was then

self-consciously metatheatrical (esp. 32-6 with nn.). An alternative possibility

is that this is commentary on the parabasis, in which Aristophanic choruses

routinely discuss their poet and even speak for him (as at e. g. Ach. 628-64;

Eq. 507-50; V. 1015-59) or attempt to explain their particular identity to the

audience (e. g. V. 1071-1121; cf. Eup. fr. 172). What is said about “Eupolis”

would then be part of the poet’s own mythic self-creation and perhaps only

tangentially related to events in the real world.

In 2, we are told that a group “was sent” (άπεστάλησαν). These individuals

are presumably identical with the ambassadors (πρέσβεις) mentioned in 10,

and also with the men who apply force (βιοισάμ(εν)οι) in 5. But who sent them,

and thus who is behind the unfriendly request in 2-3 (as restored) is obscure.

The other figure mentioned in the opening lines of the preserved portion of

the text is a comic poet (3-4), who must have been named earlier, given the

oblique reference to him in 3-5. In light of the repeated mention of Eupolis